Students & Families

After World War II, California developed the vision of higher education that made UC and CSU world leaders in their respective categories.

At UC, the idea was to combine top quality with mass access. Rather than exposing only one percent of the population to the best teaching and the most advanced research, UC would expose 10-12 times that many to the leading ideas and techniques. The result was creation of one of the most skilled and highly productive populations in history, the inventors of new technologies, popular arts, and entire industries that make California one of the most prosperous and equitable economies in the world.

A key element of economic growth is continuous improvement in productivity. Productivity rests on innovation. The innovation of a large economy depends not just on a few highly innovative people but on a generally innovative population. Each individual’s capacity to innovate comes from habits of invention rooted in active learning, confident experimentation, and intellectual risk-taking. UC developed forms of instruction suited to develop advanced skills and creativity in very large numbers of people.

A simple example has been the combination of discussion sections and lectures: the small sections are expensive, but allow students to pursue ideas in depth while receiving personalized and immediate feedback of the kind that is known to accelerate learning. One UC study of instruction called this “TIE”: the university would Transmit the knowledge base, Initiate intellectual independence, and Emphasize independent inquiry. Hundreds of thousands of students were able to benefit from this high quality of system of instruction year after year.

Elite private universities perform the same service of honing unique individual abilities, but for about 1% of the national population. As their wealth has grown, they have continued to develop customized teaching practices reflecting, as the New York Times recently reported, “research showing that most students learn fundamental concepts more successfully, and are better able to apply them, through interactive, collaborative, student-centered learning.”

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for example, has recently converted its large introductory physics lectures to small-group sections that resemble graduate seminars, thus cutting this course’s failure rate to one-third of its previous level.

The budget cuts have forced UC to move in the opposite direction: towards the “massification” of instruction that results when sections, continuous homework review, small laboratories, problem-solving sessions and similar vital practices are eliminated for lack of funds. The future of individual UC students and of California as a whole depends on maintaining the levels of instructional equality for which UC has long been renowned.

Pushing the reset button and restoring the promise of California higher education would eliminate almost all student debt for UC students

Here’s the math:

Under the Reset plan, undergraduate students would save $7,821 per year (paying $5,379 rather than $13,200 per year in tuition and fees) or $31,286 over four years. This compares to an average undergraduate student loan debt at graduation (in 2011-12) of $19,751, with only 5% of students graduating with more than $31,401 in debt (UC provides some information about the percent of students graduating with various levels of debt.)

What about CSU?

The reset plan would save CSU baccalaureate students about $2,977 per year (paying $2,495 in annual tuition and fees rather than $5,472) for a total savings of about $11,907 in four years. CSU’s average student loan debt for 2011-12 baccalaureate recipients is $18,460.

What about the effect on Community Colleges?

Under the reset scenario community college students would save about $621 per year (paying $299 per year rather than $920). The big effect on student debt by resetting community colleges, however, would not be due to cutting fees but to restoring funding for the 426,000 students pushed out of community colleges who end up in for-profit places like the University of Phoenix where they accrue huge debts and rarely have anything to show for it. All this costs taxpayers billions.

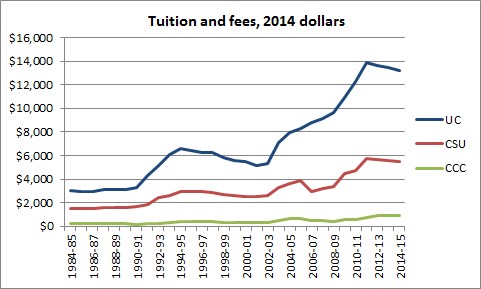

The fee increases, while very large, have not been large enough to compensate for the loss in state support.

At the same time that quality has declined, fees at UC and CSU have rapidly increased as required by the 2004 “Compact on Higher Education” that Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger imposed as part of his free-market plan to privatize public higher education by shifting the cost of “investing” in an education on to California students and their families and away from taxpayer “subsidies.”

The fee increases in the Compact were set at 10% a year, probably because that was the most that was politically possible. This amount was not related to the size of the cuts that UC and CSU accepted, resulting in a large drop in the money available to finance core functions, which were never restored.

When Schwarzenegger took office in 2003, UC had 208,000 students and the the public was providing $3.7 billion to UC (in 2014 dollars). When he left, the student body had grown to 220,000 students but the Governor was only providing $3.1 billion (again, in 2014 dollars).

And, as required by the Compact, tuition had increased from $5,530 to $12,250.

Jerry Brown cut even more.

When Governor Jerry Brown took office in 2011, he immediately cut UC another $300 million, to $2.6 billion. Since then he increased public support for UC slightly, to $2.9 billion.

Even after this modest increase, UC was still receiving $200 million less than the day Brown took office despite the fact that student enrollment had grown to over 243,000.

The net result has been a substantial drop in the quality of the educational experience, which has accelerated over time.

Restored state support is the only way to restore quality and access.

The unfortunate reality is that there are only two major sources of money to educate Californians: public money and tuition. The only realistic path to cutting tuition and restoring quality is returning to the time when the public forced Sacramento to prioritize providing high quality affordable higher education as something that the public provides for its citizens.

The only way to restore quality in the face of continuing reductions of state funding would be to substantially reduce enrollments or increase fees towards the $27,000 a year level required by privatization. Only a return to California’s historic commitment to public higher education maintains quality and access together.

Other resources:

College Board. Trends in College Pricing, 2014.

College Board. Trends in Student Aid, 2014.