The following speech by Nathan Brown, Davis Faculty Association Board Member, and Assistant Professor of English at UC Davis, was delivered at the UC system-wide strike rally held at UC Davis on November 15:

Hello Everyone!

It’s beautiful to see so many of you here today. On four day’s notice, this is an incredible turnout. Let’s remember how much we can do in so little time.

I’m an English professor, and as some of you know, English professors spend a lot of our time talking about how to construct a “thesis” and how to defend it through argument. So today I’m going to model this way of thinking and writing by using it to discuss the university struggle. My remarks will consist of five theses, and I will defend these by presenting arguments to support them.

THESES

1. Tuition increases are the problem, not the solution.

2. Police brutality is an administrative tool to enforce tuition increases.

3. What we are struggling against is not the California legislature, but the upper administration of the UC system.

4. The university is the real world.

5. We are winning.

THESIS ONE: Tuition increases are the problem, not the solution.

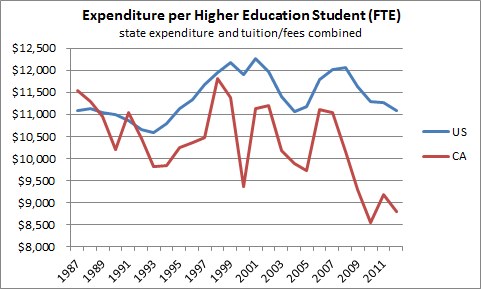

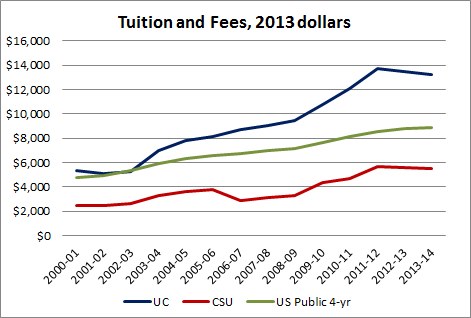

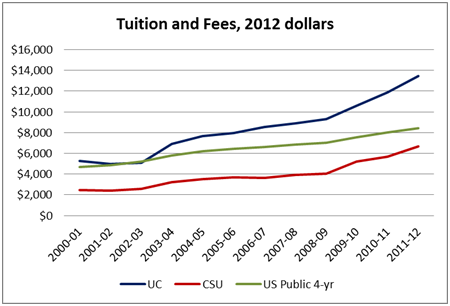

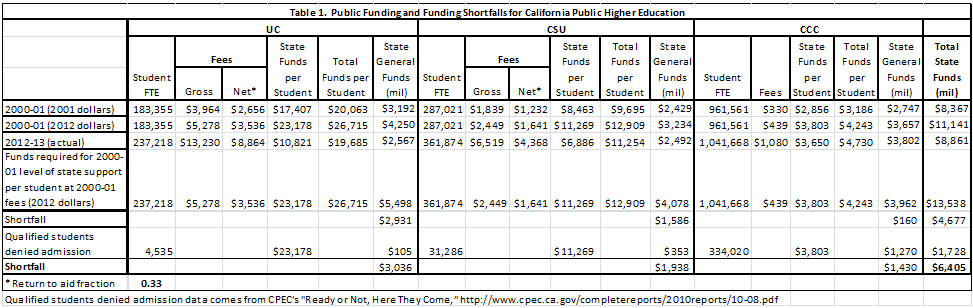

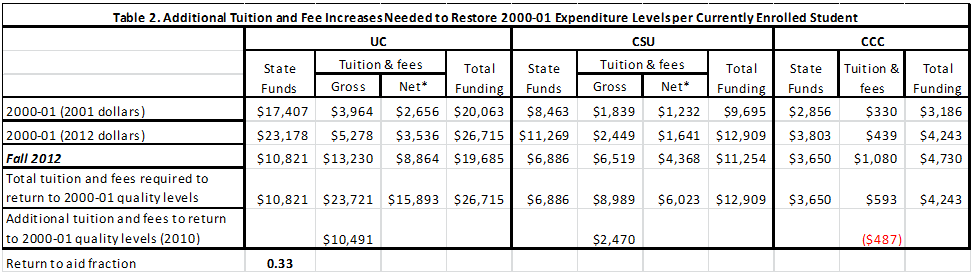

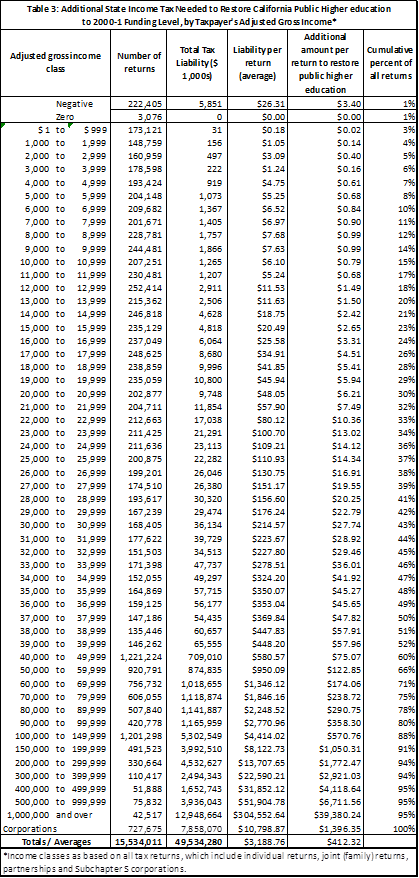

In 2005 tuition was $6,312. Tuition is currently $13,218. What the Regents were supposed to be considering this week — before their meeting was cancelled due to student protest — was UC President Yudof’s plan to increase tuition by a further 81% over the next four years. On that plan, tuition would be over $23,000 by 2015-2016. If that plan goes forward, in ten years tuition would have risen from around $6,000 to around $23,000.

What happened?

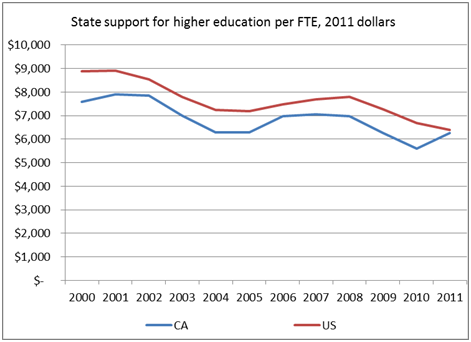

The administration tells us that tuition increases are necessary because of cuts to state funding. According to this argument, cuts to state funding are the problem, and tuition increases are the solution. We have heard this argument from the administration and from others many times.

To argue against this administrative logic, I’m going to rely on the work of my colleague Bob Meister, a professor at UC Santa Cruz and the President of the UC Council of Faculty Associations. Professor Meister has written a series of important open letters to UC students, explaining why tuition increases are in fact the problem, not the solution to the budget crisis. What Meister explains is that the privatization of the university—the increasing reliance on tuition payments (your money) rather than state funding—is not a defensive measure on the part of the UC administration to make up for state cuts. Rather, it is an aggressive strategy of revenue growth: a way for the university to increase its revenue more than it would be able to through state funding.

This is the basic argument: privatization, through increased enrollments and constantly increasing tuition, is first and foremost an administrative strategy to bring in more revenue. It is not just a way to keep the university going during a time of state defunding. What is crucial to this argument is the way that different sources of funding can be used.

State funds are restricted funds. This means that a certain portion of those funds has to be used to fund the instructional budget of the university. The more money there is in the instructional budget, the more money is invested in student instruction, in the quality of your education. But private funds, tuition payments, are unrestricted funds. This means there are no restrictions on whether those funds are spent on student instruction, on administrative pay, or anything else.

What Professor Meister uncovered through his research into the restructuring of UC funding is that student tuition (your money) is being pledged as collateral to guarantee the university’s credit rating. What this allows the university to do is borrow money for lucrative investments, like building contracts or “capital projects” as they are called. These have no relation to the instructional quality of the institution. And the strong credit rating of the university is based on its pledge to continue raising tuition indefinitely.

Restricted state funds cannot be used for such purposes. Their use is restricted in such a way as to guarantee funding for the instructional budget. This restriction is a problem for any university administration whose main priority is not to sustain its instructional budget, but rather to increase its revenues and secure its credit rating for investment projects with private contractors.

So for an administration that wants to increase UC revenues and to invest in capital projects (rather than maintaining the quality of instruction) it is not cuts to public funding that are the problem; it is public funding itself that is the problem, because public funding is restricted.

What is happening as tuition increases is that money is being shifted out of instructional budgets and into private credit markets, as collateral for loans used for capital projects. Because of this, and because of increased enrollment, as university revenue increases the amount of money spent on instruction, per student, decreases. Meanwhile, students go deeper and deeper into debt to pay for their education. Using tuition payments as collateral, the university secures loans for capital projects. In order to pay their tuition, students borrow money in the form of student loans. The UC system thus makes a crucial wager: that students will be willing to borrow more and more money to pay higher and higher tuition.

Why would students do so? Because, the argument goes, a university education is an investment in your future—because it will “pay off” down the line. This logic entails an implicit social threat: if you do not take on massive debt to pay for a university degree, you will “fall behind”—you will be at a disadvantage on the job market, and you will ultimately make less money. The fear of “falling behind,” in the future, results in a willingness to pay more in the present, which is essentially a willingness to borrow more, to go further into debt in order to make more money later.

But is it actually true that a university degree continues to give students a substantial advantage on the job market? It is now the case that 50% of university students, after graduating, take jobs that do not require a university degree. It used to be the case that there was a substantial income gap between the top 20% of earners, who had university degrees, and the bottom 80% of earners, who did not. But since 1998, nearly all income growth has occurred in the top 1% of the population, while income has been stagnant for the bottom 99%. This is what it means to be “part of the 99%”: the wealth of a very small segment of the population increases, and you’re not in it.

What this means is that the advantage of a university degree is far less substantial than it used to be, though you pay far more for that degree. The harsh reality is that whether or not you have a university degree, you will probably still “fall behind.” We all fall behind together. The consequence is that students have recently become less willing to take out more and more debt to pay tuition. It is no longer at all clear that the logic of privatization will work, that it is sustainable. And what this means is that the very logic upon which the growth of the university is now based, the logic of privatization, is in crisis, or it will be. Student loan debt is a financial “bubble,” like the housing bubble, and it cannot continue to grow indefinitely.

To return to my thesis: what this means for our university—not just for students, but especially for students—is that increasing tuition is the problem, not the solution.

What we have to fight, then, is the logic of privatization. And that means fighting the upper administration of the UC system, which has enthusiastically taken up this logic, not as a defensive measure, but as an aggressive program to increase revenue while decreasing spending on instruction.

THESIS TWO: Police brutality is an administrative tool to enforce tuition increases.

What happened at UC Berkeley on November 9? Students, workers, and faculty showed up en masse to protest tuition increases. In solidarity with the national occupation movement, they set up tents on the grass beside Sproul Hall, the birthplace of the Free Speech Movement. The administration would not tolerate the establishment of an encampment on the Berkeley campus. So the Berkeley administration, as it has done so many times over the past two years, sent in UC police, in this case to clear these tents. Faculty, workers, and students linked arms between the police and the tents, and they held their ground. They did so in the tradition of the most disciplined civil disobedience.

What happened?

Without provocation, UC police bludgeoned faculty, workers, and students. They drove their batons into stomachs and ribcages, they beat people with overhand blows, they grabbed students and faculty by their hair, threw them on the ground, and arrested them. Numerous people were injured. A graduate student was rushed to the hospital and put into urgent care.

Why did this happen? Because tuition increases have to be enforced. It is now registered in the internal papers of the Regents that student protests are an obstacle to further tuition increases, to the program of privatization. This obstacle has to be removed by force. Students are starting to realize that they can no longer afford to pay for an “educational premium” by taking on more and more debt to pay higher tuition. So when they say: we refuse to pay more, we refuse to fall further into debt, they have to be disciplined. The form this discipline takes is police brutality, continually invited and sanctioned by UC Chancellors and senior administrators over the past two years.

Police brutality against students, workers, and faculty is not an accident—just like it has not been an accident for decades in black and brown communities. Like privatization, and as an essential part of privatization, police brutality is a program, an implicit policy. It is a method used by UC administrators to discipline students into paying more, to beat them into taking on more debt, to crush dissent and to suppress free speech. Police brutality is the essence of the administrative logic of privatization.

THESIS THREE: What we are struggling against is not the California legislature, but the upper administration of the UC system.

It is not the legislature, but the UC Office of the President, which increases tuition in excess of what would be necessary to offset state cuts. Again, tuition increases are an aggressive strategy of privatization, not a defensive compensation for state cuts. When we protest those tuition increases, it is the Chancellors of our campuses, not the state legislature, who authorize police to crush our dissent through physical force. This is why our struggle, immediately, is against the upper administration of the UC system, not against “Sacramento.”

This struggle against the administration is not about attacking individuals—or not primarily. It is about the administrative logic of privatization, and the manner in which that logic is enforced. We need to hold administrators accountable for this logic—and especially for sending police to brutalize students, workers, and faculty. But more importantly we need to understand and intervene against the logic of privatization itself: a logic which requires tuition increases, which requires police brutality, in order to function.

This is why the point is not to talk to administrators. When we occupy university buildings, when we disrupt university business as usual, the administration attempts to defer and displace our direct action by inviting us into “dialogue”—usually the next day, or just…some other time. What these invitations mean, and all they mean, is that the administration wants to get us out of the place where we are now and put us in a situation where we have to speak on their terms, rather than ours. It is the job of the upper administration to push through tuition increases by deferring, displacing, and, if necessary, brutally repressing dissent. The program of privatization depends upon this.

The capacity of administrators to privatize the university depends on their capacity to keep the university running smoothly while doing so: their capacity to suppress any dissent that disrupts university operations. The task, then, of students, faculty, and workers, is to challenge this logic directly. The task is to make it clear that the university will not be able to run smoothly if privatization does not stop. In many different ways, since the fall of 2009, we have been making this clear.

THESIS FOUR: The university is the real world.

The university is not a place “cut off” from the rest of the world or from other political situations. The university is one situation among many in which we struggle against debt, exploitation, and austerity. The university struggle is part of this larger struggle. And as part of this larger struggle, the university struggle is also an anti-capitalist struggle.

Within the university struggle, this has been a controversial position. Rather than linking the university struggle to other, larger struggles, many have argued that we need to focus only on university reform without addressing the larger economic and social structures in which the university is included—in which the logic of privatization and austerity is included, and in which the student struggle is included. But to say that the university struggle is an anti-capitalist struggle should now be much less controversial, and it should now be much easier to insist on linking the struggle against the privatization of the university to other anti-capitalist struggles.

The Occupy Wall Street movement, which has become a national occupation movement, makes this clear. All across the country, from New York to Oakland to Davis, in hundreds of cities and towns, people who have been crushed by debt are rising up against austerity measures that impoverish them further. The national occupation movement and the UC student struggle are parts of the same struggle, which is global. It is articulated across political movements in Greece, in Spain, in Chilé, in the UK, in Tunisia, in Egypt, etc. This is a struggle against the destruction of our future, in the present, by an economic system that can now only survive by creating financial bubbles (the housing bubble, the student loan bubble) which eventually have to pop.

Two years ago, positioning the UC struggle as an anti-capitalist struggle was seen as divisive. The argument was that such a position was alienating and that it would inhibit mass participation. But now we see that there is a mass, national movement which is explicitly anti-capitalist, which positions itself explicitly as a class struggle, and, in doing so, struggles against debt and austerity as the interlinking financial logics of a collapsing American economy. Given this context, the only way the university struggle can isolate itself is by failing or refusing to acknowledge that it is also an anti-capitalist struggle, that it is also a class struggle.

This struggle concerns all of us, faculty as well as students and workers, because the economic logic of privatization, the logic of capitalism, destroys the very texture of social life in our country and around the world, just as it destroys our public universities.

“We are all debtors,” said a student at Berkeley as she called for this strike. That is a powerful basis of solidarity.

THESIS FIVE: We are winning.

Yes, it is true that tuition continues to rise. I am not saying that we have won. But it is also the case that last year state funding was partially restored. This was due to student resistance on our campuses, not in Sacramento. It was due to our struggle against the administrative logic of privatization. Meanwhile, privatization is becoming more and more unsustainable, less and less viable. In the fall of 2009, student resistance became a powerful obstacle to perpetually increasing tuition. It is because of that obstacle that the Regents meeting was cancelled this week.

But even more important than these immediate gains is the fact that we have built the largest and most significant student movement in this country since the 1960s. UC Davis has played an important role in building that movement. The 2009 student/faculty walkout was initiated by people on this campus. The occupations of Mrak Hall in November 2009 and the courageous march on the freeway on March 4 2010 have been tremendously inspirational to students struggling on other campuses. Actions like these are the very material of which the student movement consists. Without them it would not exist.

So we have built a historically important student movement, and now that movement is linked to largest anti-capitalist movement in the United States since 1930s. Students now have the support of a struggle that can be waged on two fronts, on and off campus.

To put it mildly, we have many more allies than we did two years ago.

At the same time, the UC student movement has had a global impact. The tactic of occupation that was crucial to the movement in the fall of 2009, which spread from campus to campus that November, has now also spread across the country. The occupation of university buildings is a time-honored tactic in student struggles. But by many it was also viewed as a “divisive” or “vanguardist” tactic two years ago. Now, thanks largely to the example of the Egyptian revolution, the occupation of public space has become the primary tactic in a national protest movement supported by some 60% of the American people. The mass adoption of this tactic, the manner in which it has grown beyond the university struggle, is a huge victory for our movement.

Here is a passage from an influential student pamphlet written in 2009, Communiqué from an Absent Future: On the Terminus of Student Life, which was read by people across the US and translated into six different languages:

Occupation will be a critical tactic in our struggle…and we intend to use this tactic until it becomes generalized. In 2001 the Argentine piqueteros suggested the form the people’s struggle there should take: road blockades which brought to a halt the circulation of goods from place to place. Within months this tactic spread across the country without any formal coordination between groups. In the same way repetition can establish occupation as an instinctive and immediate method of revolt taken up both inside and outside the university.

People at Adbusters, the Canadian magazine which initially organized the Occupy Wall Street protests, read that student pamphlet and wrote about it in 2009. The tactic that pamphlet called for was put into practice across the UC system, under the slogan “Occupy Everything,” and the goal of spreading that tactic has been unequivocally achieved. Its achievement has had huge political implications for the whole country. So this is also a way in which we are winning.

Occupation has been and continues to be such an important tactic because it is not limited to the university, but linked to occupations of squares and plazas in cities, and linked to struggles to begin occupying foreclosed properties on a mass scale. The resonance of university occupations with the national occupation movement means that our struggle is growing and expanding. That means we are winning. And the fact that the university struggle can no longer plausibly be considered in isolation from anti-capitalist struggle broadly conceived is itself a huge victory.

We cannot simply change “the university” while leaving “the world” as it is, because the university is the real world. By changing the university, we change the world. And we have to change the world in order to change the university.

Posted: November 16th, 2011, by: admin. Categories: Uncategorized. 1 Comment.