How much will it cost us to restore public higher education in 2012-13?

This working paper has been superseded by an updated version:

How much will it cost us to restore public higher education in 2013-14?

Read “Financial Options for Restoring Quality and Access to Public Higher Education in California” below or download a PDF of it (November 2012, 7 pp.) If you’re really a policy wonk, download the spreadsheets behind this report.

WORKING PAPER

FINANCIAL OPTIONS FOR RESTORING QUALITY AND ACCESS TO PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATION IN CALIFORNIA: 2012-13

Stanton A. Glantz

Professor of Medicine

American Legacy Foundation Distinguished Professor in Tobacco Control

University of California San Francisco

Chair, University of California Systemwide Committee on Planning and Budget (2005-6)

Vice President, Council of UC Faculty Associations

glantz@medicine.ucsf.edu

Eric Hays

Executive Director of, Council of UC Faculty Associations

info@cucfa.org

(November 10, 2012)

Council of UC Faculty Associations

1270 Farragut Circle

Davis, CA 95618

Phone: (888) 826-3623

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

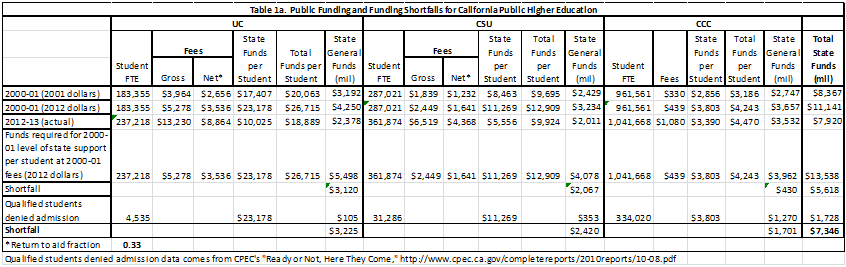

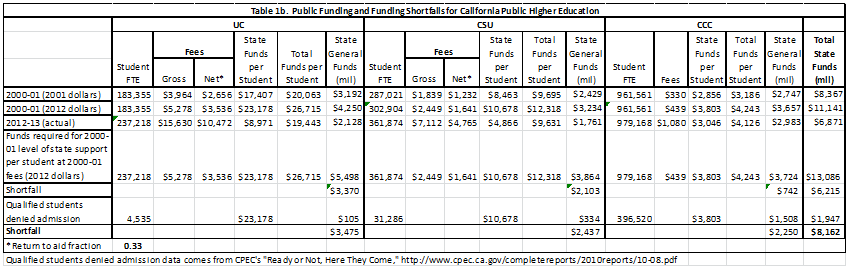

It is widely recognized that large reductions in state funding and sizeable increases in student fees have eroded quality and accessibility in California’s three-segment system of public higher education: the University of California, California State University and California Community Colleges. This report estimates what it would cost – through restored taxpayer funding or tuition increases — to restore the system’s historic quality while accommodating the thousands of qualified students excluded by recent budget cuts. This working paper considers state funding, student fees and accessibility to answer three basic questions about the public higher education system in California:

#1. How much would it cost taxpayers to push the “reset” button for public higher education, restoring access and quality (measured as per-student state support) while rolling back student fees to 2000-01 levels, adjusted for inflation?

Answer: It would cost taxpayers $7.346 billion.

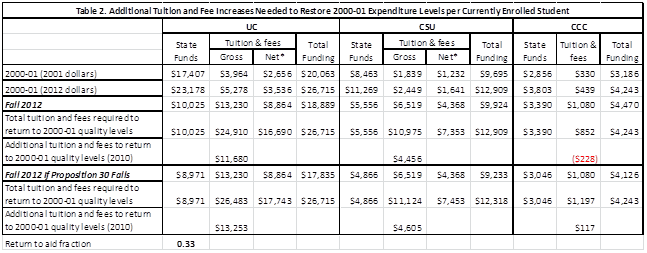

#2. Absent restoration of taxpayer support for public higher education, how much more would student fees need to be increased to restore the level of per-student resources available in 2000-01?

Answer: University of California fees would have to increase over the current year’s fees by $11,680 (to a total of $24,910 per year), California State University fees would have to increase by $4,456 (to a total of $10,975 per year); California Community College fees would not have to increase.

#3. If the Governor and Legislature were to decide to push the “reset” button — reinstating the quality and accessibility standards of the Master Plan by returning state support and student fees to 2000-01 levels, adjusted for inflation — what would it cost the typical California taxpayer?

Answer: It would cost the median California taxpayer about $55.

Introduction:

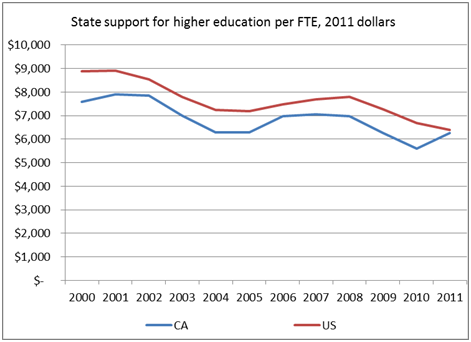

It is widely recognized that beginning with Governor Gray Davis’ 2001-2 budget year, accelerating with Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Compact for Higher Education,[1] and now continuing under Governor Jerry Brown, higher education in California has suffered large reductions in state funding. These reductions have effectively abandoned the California Master Plan for Higher Education[2] promise of high quality, low cost public higher education for all through an articulated system consisting of the University of California, California State University and California Community Colleges. California has consistently spent less than most states per higher education student (Figure 1).

Data: State Higher Education Executive Officers, http://www.sheeo.org/finance/shef-home.htm

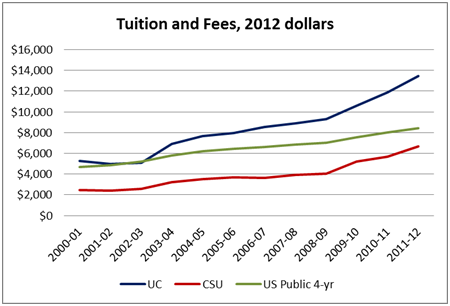

At the same time, fees at UC and CSU have increased much faster than at colleges in the US as a whole (Figure 2). While these fee increases have generally been framed as responses to the State’s immediate budgetary problems, they are also congruent with the explicit public policy choice, based on free market principles and embodied in Governor Schwarzenegger’s Compact for Higher Education, to shift higher education from a public good provided by society as a whole through taxation to being a private good purchased through user fees.

Source: College Board, table 4a of http://trends.collegeboard.org/college_pricing/

This shift in public policy is stated in the 2004 Compact on Higher Education between Governor Schwarzenegger and the UC President and CSU Chancellor: “In order to help maintain quality and enhance academic and research programs, UC will continue to seek additional private resources and maximize other fund sources available to the University to support basic programs. CSU will do the same in order to enhance the quality of its academic programs.” Until this point, the state was the primary source of support for “basic programs” with private sources being used for additional initiatives.

This working paper ties together the three elements of change: drops in state funding, fee increases, and declines in quality (measured as per student expenditures). It takes as its base year 2000-01, the last year that higher education was reasonably financially intact before the recent large fee increases. This paper addresses three questions:

- How much would it cost taxpayers to push the “reset” button for public higher education, restoring access and quality (measured as per-student state support) while rolling back student fees to 2000-01 levels, adjusted for inflation?

- Absent restoration of taxpayer support for public higher education, how much more would student fees need to be increased to restore the level of per-student resources available in 2000-01?

- If the Governor and Legislature were to decide to push the “reset” button — reinstating the quality and accessibility standards of the Master Plan by returning state support and student fees to 2000-01 levels, adjusted for inflation — what would it cost the typical California taxpayer?

Answer No. 1: Returning quality and fees to the level of 2000-01 would cost taxpayers $7.346 billion.

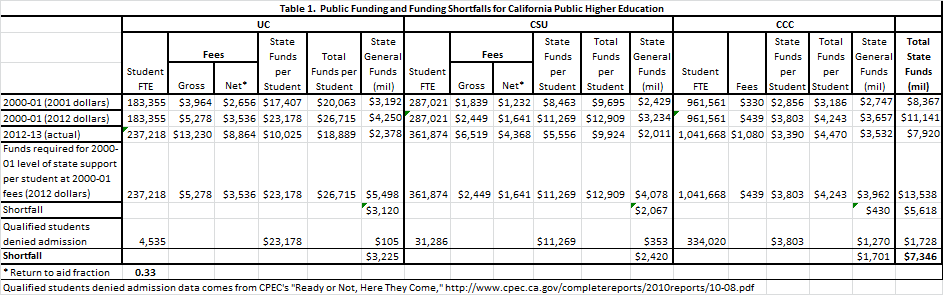

By restoring state funding to 2000-01 levels, it would be possible to return student fees to the levels of 2000-01 (adjusted for inflation) while maintaining quality (measured as total per student funding). Specifically, annual fees at UC would be rolled back to $5,278 (from $13,230), for CSU to $2,449 (from $6,519) and for CCC to $439 (from $1,080).

Table 1 shows the calculations that produced this number.[3] We begin with the number of full time equivalent (FTE) students in each of the three sectors of California higher education and total state general funds supplied to each sector,[4] then divide one by the other to obtain the state funding per student FTE. Next we adjust the 2000-01 dollar amounts for inflation to their equivalents for 2012-13 and subtract the actual levels of funding per student currently enrolled in each sector to determine the funding shortfall compared to 2000-01.

Restoring full state funding for existing enrollments would cost a total of $5.618 billion. These calculations do not tell the whole story, however, because all three sectors have responded to resource cuts by admitting fewer students than they would under the Master Plan. Providing funding to accommodate students who have been forced out of the higher education system would raise this number to $7.346 billion.

Answer No. 2: Restoring the public higher education system for all students only by increasing student fees would require raising UC fees an additional $11,680 (to a total of $24,910 per year), and CSU fees by $4,456 (to $10,975 per year). CCC fees would not have to increase.

Table 2 outlines the calculations that led to these numbers. The overall approach is the same as in Table 1, except that rather than restoring per student total expenditures by increasing state support, it is done by increasing student fees. Calculations for UC and CSU assume that it continues its “high fee high aid” policy of allocating 33 percent of fees to student aid.[5] The total funding per student used as a measure of quality is the sum of state funding and net tuition and fees after deleting the fee amounts returned to aid.

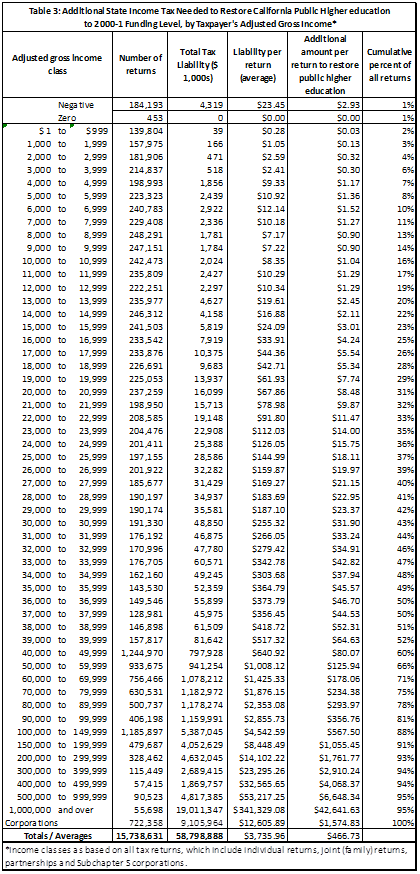

Answer No. 3: Restoring public higher education while returning student fees to 2000-01 levels would cost the median California taxpayer an additional $55.

Table 3 outlines these calculations. We obtained the distribution of taxes paid by adjusted gross income per tax return from the Franchise Tax Board 2009 (for tax year 2008),[6] the most recent year available, then allocated the $7.346 billion it would cost to restore public higher education to 2000-01 proportionately across all taxpayers. Note that the categories are for tax returns, not individuals, so the results are for joint returns (families), individual returns, partnerships and Subchapter S corporations, as well as corporations that pay income taxes. Thus, the numbers per taxpayer (as opposed to tax return) for joint returns would be half the numbers in Table 3.

For the median personal income tax return, restoring California’s entire higher education system while rolling back student fees to what they were a decade ago (adjusted for inflation) would cost $55 next April 15. For the two-thirds of state tax returns with taxable incomes below $60,000, it would cost $141 or less. Tax returns with the top 5% of adjusted gross income — $400,000 to $499,999 – would increase by $4,723.

It is also worth noting that our income tax distribution data lags our other data by several years and is just now falling into the deficit (2008 year data), which has an effect on the calculation of the median return. For comparison, using 2007 year data the median return would pay $45 to restore higher education in 2012-13. Certainly in 2012 the state’s economy looks a lot better than it did in 2008, so the actual cost to the median return is likely lower than $55.

Income taxes are presented as one option, simply to illustrate the cost for typical taxpayers. Personal and corporate income taxes are only 70 percent[7] of all state revenues; part of the $7.346 billion could be allocated to other taxes, which would lower the effect on individual income tax payers. We also assume that the costs would be distributed uniformly across all tax categories. If the cost were allocated more or less progressively, that would also affect impact on individual taxpayers.

Limitations:

The calculations outlined in this working paper are all based on publicly available numbers and do not benefit from models of enrollment dynamics that may be maintained by state agencies or the three segments of the California public higher education system. The estimates do not account for price elasticity: as tuition and fees increase, some students decide not to attend public higher education in California, which will reduce student demand. We assume, based on public statements and documents, that enrollment at California’s public higher education institutions has been constrained by their budgets. Finally, the distribution of taxes is based on a 2009 report of tax year 2008, the most recent time for which data are available; this distribution will be different in 2012.

These calculations will be updated and subsequent versions of this Working Paper will be released as better data become available.

[1] The full text of the Compact has now been removed from the budget.ucop.edu site, but we have a copy of it at http://clearsighted.com/keepcaliforniaspromise.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/2005-11compactagreement1.pdf.

[2] The full text of the Master Plan is at http://www.ucop.edu/acadinit/mastplan/MasterPlan1960.pdf. For a discussion of the history and current status of the Master Plan, see Legislative Analyst Office, “The Master Plan at 50: Assessing California’s Vision for Higher Education,” November, 2009, available at http://www.lao.ca.gov/laoapp/PubDetails.aspx?id=2141.

[3] The spreadsheet used to obtain all the results in this working paper is available at http://keepcaliforniaspromise.org/

[4] Student FTE data comes from the individual higher education systems, state expenditure data comes from the Legislative Analyst’s Office available at http://lao.ca.gov/laoapp/LAOMenus/lao_menu_economics.aspx and supplemented for recent years by the Governor’s 2012 budget: http://www.ebudget.ca.gov/StateAgencyBudgets/6013/agency.html

[5] See page 16 of http://www.assembly.ca.gov/acs/committee/c2/hearing/2005/april%2020%20%202005-uc%20csu-%20public-%20cm.doc.

[6]State income tax revenue by adjusted gross income class and state income tax revenue from corporations: http://www.ftb.ca.gov/aboutFTB/Tax_Statistics/2009.shtml

[7] Governor’s Budget Revenue Estimates: http://www.ebudget.ca.gov/pdf/BudgetSummary/RevenueEstimates.pdf