An Open Letter to UC Students

From Bob Meister,

President, Council of UC Faculty Associations

Professor of Political and Social Thought, UC Santa Cruz

(Download a PDF version of this document or view a one page summary.)

As students, you pay tuition in order to get an education at UC, and you know that the Regents plan to raise your tuition even higher. You may think that the tuition you pay is primarily or exclusively used for instruction, but this is not its only use. UC recently sold more than $1.6B in highly rated bonds one month after declaring an “extreme financial emergency.” Why is its bond rating excellent, even after UC says that without cutting employee pay it will have difficulty paying its bills? The single most important reason that UC has an excellent bond rating, much better than the state’s, is that it can now raise your tuition at will. Your tuition is UC’s #1 source of revenue to pay back bonds, ahead of new earnings from bond-funded projects, which do not even come second. The bond interest UC now pays will be $300M this year, and is projected to go way up as UC greatly increases the private capital it raises through tuition-backed bonds over the next decade. UC should disclose its plans to issue new tuition-backed bonds before you are asked to accept this year’s 32% tuition increase, which will automatically become part of the collateral for those bonds.[1]

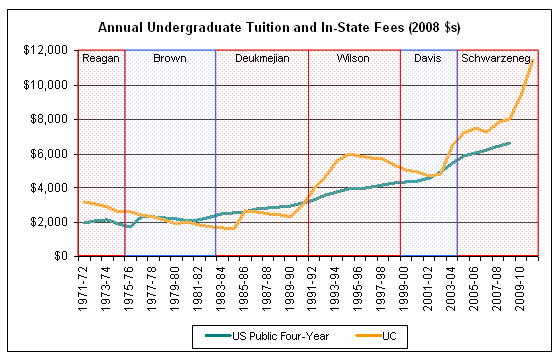

Because UC pledges 100% of tuition to maintain its bond rating, it has also implicitly assured bond financiers that it will raise your tuition so that it can borrow more. Since 2004, UC has based its financial planning on the growing confidence of bond markets that your tuition will increase. (Why? Because you’ve put up with this so far, and because UC has no other plan. Its capacity to raise tuition is advertised in every bond prospectus.)

(Before I go on, you should understand that there’s a difference between using your tuition as collateral for construction bonds and actually spending to pay the interest on those bonds. UC now spends some tuition revenue on debt service, and is likely spend more for this purpose as it borrows more against tuition. Since 2004, all of your tuition has been pledged in the sense that it will be paid into an account held by the bond trustee in the event of default.)

In pledging all your tuition as collateral for its bonds, UC is relying on a simple notion which, if used by an individual trying to borrow money, would go like this: if you had a good paycheck and you expected to have steady raises in the future, you could pledge your whole paycheck to secure a loan. Your bank might offer you a lower interest rate for pledging it all without expecting you to use it all to service your debt. You could then still live off your paycheck as well as get a lower interest rate. UC has done just that with your tuition. It considers itself smart to have made this kind of deal. In 2008 it paid 0.2% less in interest for bonds backed by tuition (and all General Revenues)[2] than for bonds funded by project revenues alone, such as those that paid for employee parking garages.

So, one reason that UC has pledged all of your tuition, including future hikes, may have been to get a better interest rate, and that is likely to be the explanation it gives publicly. But is lowering interest rates the only reason why UC pledged your tuition?

In fact, there are stronger explanations that are less benign. The first is that, although tuition can be used for the same purposes as state educational funds, it can also be used for other purposes including construction, the collateral for construction bonds, and paying interest on those bonds. None of the latter uses is permissible for state funds, so the gradual substitution of tuition for state funds gives UC a growing opportunity to break free of the state in its capital funding. A second explanation for the tuition pledge is based on the idea that a bank will pay less attention to whether you’re making a good investment if it has access to your entire paycheck in the event you haven’t made a good invetment. This means that UC can be much less transparent about how much revenue it earns from tuition-backed bonds, which are now more than half of its total borrowing and are expected to greatly exceed all other borrowing over the next decade. A third explanation for including your tuition in the pledge is that tuition is expected to rise no matter what happens, and is likely to go up even faster in bad budget years. UC’s pledged collateral rose by 60% ($4.2B to $6.72B) from the last pre-Schwarzenegger year through June 2008. Tuition, a large and growing component of that collateral, has risen much faster since the state economy collapsed in 2008–it will be up 109% by Spring 2010 We won’t know the effect of recent increases on UC’s total collateral until its next two financial statements come out, but it appears that UC has nearly doubled its borrowing against that collateral in 2009 alone. The fact that UC can (and does) raise tuition during state economic crises means that a bad budget year can be a good bond year.

Why haven’t you been told that UC has been using your tuition as collateral to borrow billions of dollars? The obvious reason is that tuition increases are justified (to you) as a way to pay instructional expenses that taxpayers refuse to pay. If that’s why they’re being imposed, it’s natural to assume that tuition increase will be used to minimize cuts to education. But when UC pledges your tuition to its bond trustee (Bank of NY Mellon Trust), it’s really (legally) saying that your tuition doesn’t have to be used for education, or anything in particular. That’s why it can be used to back UC construction bonds, and why the growth in tuition revenue, as such, is enough to satisfy UC’s bond rating agencies (S&P and Moody’s), whether or not UC can pay its bills. The effect of UC’s pledge is to place a new legal restriction on the use of funds that it must first say it could have used for anything, including education. Thereafter, construction comes ahead of instruction.

Some of UC’s new, and self-imposed, constructions costs will come off the top of its annual budget, despite this year’s “extreme financial emergency.” When UC chose t0 take on $1.35B in new construction debt for 70 projects in August 2009—one month after imposing employee furloughs that “saved” $170M—it committed to spending $70-80M in extra interest payments for years into the future –they’ve just released the interest rates for each new bond series. Earlier in the year, UC had already issued $.8B in tuition-backed bonds in spring 2009, only some of which were for refinancing older projects at lower interest rate. It’s thus likely that the interest due on new projects funded during 2009 alone will have eaten up more than half of UC’s “savings” from the furloughs. Would the furloughs have been “unavoidable” if UC were not secretly planning to incur additional interest expenses for new bond-funded construction? I’ve just today (October 9) received a list of the 70 tuition-funded projects that were not announced until after the furloughs, and that UC decided not to postpone in order to avoid furloughs. These projects are listed at the end of this document. You can judge for yourself how urgent they are, and how high your tuition would go to finance more like them.

Interest payments are not the only cost of issuing bonds that comes off the top of UC’s budget: there are also reserves. UC’s Bond Indenture provides for reserves to be held in the name of UC’s bond trustee (BoNYMellonTrust ), even while allowing the Regents to control the larger accounts maintained to pay for actual construction and to avoid holding reserves for interest alone. Do these trustee-held reserves (which can’t be spent for other purposes) show up in UC’s audited financial statement? There is a line reporting that “non-current assets held by trustees” as of June 30, 2008 were $753M—a number, perhaps coincidentally, close to UC’s current-year shortfall in state funds. Does this line refer to the bond trustees? If so, how much higher will this number be as a result of this year’s $2.5B in newly-issued bonds? President Yudof knows. He could have had this line in UC’s Financial Statement in mind when he threw off a number of $900M in apparently “unrestricted” reserves that he says are really earmarked for construction.[3] But he could have been referring, instead, to a separate construction fund, held by the Regents, or to their deposit in its common pool of reserves (called STIP), which in recent years has totaled up to $6B, and could have swelled even higher as a result of UC’s 2009 bond issues. The bottom line is that you should demand further disclosures about UC’s bond-related reserves.

A further question is the extent to which UC promised to manage its budget so as to protect its bond rating. The “due diligence” documents that UC should have furnished to the bond trustee( BoNYMellon) and the bond ratings companies (S&P and Moody’s) would normally address the “best-” and “worst-” case scenarios. If UC prepared such documents, they might well contain assurances, made as early as the first bonds issued 2004, about what UC would do when its state funding fell to present levels, These reductions were already anticipated, although not quite this soon. If so, these documents would explain, in a concrete way, why President Yudof now says that he had to cut pay (i.e., impose furloughs) and raise fees (especially tuition) as evidence that UC’s bonds are still good, indeed better than ever. The trust and ratings companies won’t release the documents UC furnished to get its bond rating, but President Yudof could do so. You should demand UC’s “due diligence” documents before you accept the claim that UC is raising your tuition as a matter of necessity, rather than as a choice to put construction first.

Even without such disclosures, UC’s shift in priorities from state-funded instruction to privately-funded construction is hidden in plain sight – in the text of the General Revenue Bond Indenture . The Indenture says (presumably the language is standard) that the Regents, in addition to avoiding default, “shall not permit to be done anything that might in any way weaken, diminish or impair the security intended to be given pursuant to the Indenture”[4] (italics added). You would be foolish to regard this as meaningless lawyer-talk that leaves funding higher education intact as UC’s highest budgetary priority. It, rather, makes UC’s bond rating its highest budgetary priority.

The shift in priorities reflected in UC’s General Revenue bonds is even more important than the off-the-top costs, which will certainly rise over the decade unless UC’s priorities are reversed. The concept of a “General Revenue” bond is a hybrid between a “general obligation bond” and a “revenue bond,” and is as close as UC can come to backing each individual project with all it revenues without having the power to tax—although the power to raise fees comes close. By pledging “General Revenues” (everything it can legally pledge) for every project UC thus changed its spending (aka “budget”) priorities to suit the bond market. This shouldn’t be surprising—you, too, would change your spending priorities to suit that bank if you pledged your entire paycheck, or as much of it as you could.[5] For UC this means increasing tuition for its own sake, because every tuition dollar can be added directly to the pledged collateral. It also means cutting spending when and where it can get away with doing so. What this is means is that state budget cuts are actually good for UC’s bond rating, because they allow UC to raise tuition simultaneously. Construction funding is a reason why the Regent’s want to raise tuition, perhaps the most important reason, but, as students, you are unlikely to go along with big increases to fund UC’s list of construction projects. Cutting back on instructional budgets is how they get you to agree to higher tuition without telling you how much will go to fund construction. On my campus, the most visible instructional cuts typically become permanent, and we’re told that without higher tuition they would have been worse. Campus administrations can always say that no particular tuition increase is ever large enough to reverse whatever instructional cuts were imposed to persuade you that it was necessary. If you accept this claim, you’ll never question how much of your tuition is used to fund construction, and whether you would have found an increase justified had you known.

To people in the financial world, it’s already obvious that UC committed itself to raise tuition and cut budgets when it decided in 2004 to secure its bonds. Most of my UC colleagues—faculty, students and staff—nevertheless find it unthinkable that UC would actually raise tuition and cut instruction in order to fund construction. People understand that UC wants to build. What’s unthinkable is that UC would still want to build rather than protect its programs and people when other great universities, including Harvard, indefinitely postponed new construction when their endowment income fell. Why? Because protecting people and programs seem to be a higher priority for Harvard than for UC.

Obvious? Unthinkable? UC’s actions are both. The Regents were under no legal obligation to spend any of your tuition on education—that’s why they can promise to turn the entire amount over to bondholders in the event of default. But neither were they obliged to pledge every penny of your tuition (all its other available revenue) in order to protect their borrowing power in capital markets. President Yudof could be referring to UC’s bond rating when he says that all UC’s “unrestricted” funds are “tied up or must be maintained at a certain amount for the fiscal health of the university.”[6] Those of you who have skipped my footnotes should note that the title of his piece is “Why UC Must Raise Tuition.”

What UC has done was not inevitable, and went far beyond anything that the world of bond financing could have legally required of it. Before you go along with this year’s increase of 32% (which is compounded over last year’s increase), you should ask whether UC promised to manage its budget (your education) so as not to lower its bond rating.

It should be unthinkable that the Regents could have made such a commitment in 2004.[7] To think that they actually did this means that, since 2004, UC’s highest priorities have been set by bond raters, and not by the State of California. I’m going public with my concerns about what this means for you, the students of our university, because I’m tired hearing that it will always be too soon to protest UC’s privatized future until it is already too late. By then, “the inevitable” will have happened by a thousand cuts, and taxpayers will believe that UC is determined to privatize no matter how much money it gets from the state. I, thus, see no point in waiting to know more before urging you to say “no” to the November tuition increase. More information won’t persuade my more cautious colleagues who think now is never the time to reverse the trend toward privatization—not even during a budget crisis when jobs are on the line, much less during good times when funds are flowing.

UC has a leadership problem, a problem of direction. So, yes, your tuition is pledged to finance UC’s plans to raise increasing amounts of capital in bond markets, and you should know what these plans are before paying more in tuition. I’ve made a further calculation in deciding that this is the right time for you to question UC’s leadership. If UC’s leaders can answer your questions by showing that the net budgetary impact of tuition-backed bonds is thus far relatively small, then you still have time to reverse their direction. If they are planning to greatly increase the funds raised by such bonds by rapidly raising tuition, this means that your time is running out.

Based on what I’ve said thus far, here’s why you should conclude that now is the time to demand full accountability from UC, and each of its campuses:

- UC’s off-the-top diversion of funds from instruction budgets to construction finance is not transparent in any document available to you, the general public or even to me. (I’ve recently seen such a document, but was not allowed to keep it or take notes.)

- Had the full extent of UC budgetary diversion for construction been transparent, this year’s “emergency” cuts and fee increases would have appeared as what they were, a choice of priorities, rather than inevitable.

- UC’s most recent (post-“emergency”) construction bonds are just the beginning of a long-term (10-15 year) plan to borrow very much more against very much higher tuition in order to fund individual projects that no longer have to be approved by the state or paid for out of each project’s own revenue. The next step in this direction is this year’s 32% tuition increase, which the Regents plan to approve in November.

- Before you accept this, yet again, you need to find out how much of this additional tuition revenue will be diverted for construction and how UC’s shift from state funded to tuition-funded construction finance has affected its priorities as a still-public university – and in particular, how it will affect its ability to deliver the first class education you came her to obtain. Is UC simply raising your tuition because it can, and because doing so automatically increases the collateral available for its bonds?

Some UC apologists will dismiss such questions about UC’s priorities, saying they are based on the naïve assumption that all your tuition money should go to the classroom, rather than, for example, research. In giving such an answer, they would be holding back a crucial piece of information that appears in UC’s non-public documents, which explicitly say that taxing research overhead is the #2 source of repayment funds for General Revenue bonds. This doesn’t mean that new buildings will be paid for by the additional research overhead they “earn.” Even federal grants, which pay UC the maximum “overhead” it gets from anyone, expect UC to “share” (i.e., eat) about 10% of the full budgetary cost on the grounds that doing research should be one of UC’s priorities.[8] But once you see that no UC research ever fully pays for itself, you’ll see that UC must be assuming that all new research labs will add more costs than revenues. The bond documents don’t say that new projects will generate surplus revenue that could be used to support instruction: they are not like private sector “investments” that return a profit to the enterprise. Each new capital project that UC finances on its own, without state subsidy, is at best break-even. Most will be a permanent (perhaps growing) drain on campus resources that will be covered, first, by raising your tuition, second by spreading existing research support funds even thinner, and third by charging you more for other things, like student activities, while giving you less. The list goes on, but what you need to know is that even UC’s new research labs and sports facilities can’t be justified by how much new revenue they bring. Even if they earn some revenue, they’re being built for the prestige of the campuses (and thus the Chancellors) with no disclosure about how much they add to costs, how much tuition will be raised as a result, and whose instructional and research support budget will be cut.

UC has responded to criticism of its post-“emergency” bond issues by simply saying (to the press and on its website) that it would be irresponsible to issue bonds without having a revenue source to pay them back. You shouldn’t be bamboozled by this vague, well-crafted statement into assuming that this revenue source comes mainly from the bond projects themselves. It comes mainly from your tuition, and UC’s ability to raise it at will and, secondarily, from its ability to cut at will what it actually spends on instruction and on overhead support for researchers. As a result, it’s simply misleading for UC’s website to suggest that it can’t use these bonds to pay the costs of keeping class size down, keeping libraries open, preserving student access to lab courses, maintaining staff support for classroom instruction, and retaining the high quality faculty who make UC a magnet for California’s best students. UC now gets more than half of the revenue added by each new student from tuition, rather than from the state—and it expects tuition to rise as state funds decline. It is fine for UC to say that it won’t use the bonds to support instruction because the state underfunded enrollments by $122M, or that it shouldn’t pay for operating costs by borrowing. I’m not saying that it should. But, if it shouldn’t, this bears on the question of how much tuition should increase, and whether tuition-backed bonds should be used primarily to fund buildings that will be used primarily for instructional purposes. I’m open to the argument that using tuition to finance buildings devoted to cutting edge research might be justified by the prestige and value of the work done in them, but I doubt that this is true of the administrative and service buildings that may already be covered by voter-approved state bonds for which UC is unwilling to wait, even though recent layoffs have left it with a lot of unused space.

UC’s 2004 decision to become tuition funded for both its budget and its capital projects reflects a fundamental change in its priorities and purpose that goes far beyond anything the world of bond financing could require.

- The first way to understand this shift is conceptual: you need to grasp the fact that the revenue a public university raises through tuition (unlike its funding from the state) can be used as collateral to borrow capital markets. This means that a public university deciding to privatize will value tuition dollars more highly than state dollars—partly because it can more easily financialize tuition, and partly because the process of becoming tuition-dependent allows it to simultaneously blame all budget cuts on the state, and the fact that it can’t raise tuition enough.

- A second way to understand this shift is through its direct effect on your finances: a privatizing university will generate the higher tuition used to finance capital projects by requiring you (its median student) to borrow the same money from the home mortgage and student loan industries. It is, thus, requiring you to support UC’s excellent bond rating by taking on personal debt backed by your own credit rating. This is a surreal form of credit swap in which UC funds new construction by getting your parents to risk foreclosure and you to risk insolvency for much of your adulthood. In return UC takes on the risk of what? There are several scenarios, but most end with the risk of having to accept non-California students who can pay higher tuition to replace California students who can’t or won’t borrow enough to finance higher tuition. Such a “swap” works mainly to UC’s advantage, not yours, unless you would otherwise have taken on just as much debt for a worse purpose.[9] This is yet another way in which UC is becoming debt-financed rather than taxpayer-financed.

- A third way of understanding UC privatization is budgetary: that it shifts UC’s spending priorities away from what the state will fund and toward producing revenue streams that it can treat as capital assets.[10]

- A fourth way of understanding UC privatization is political in the sense that UC leaders now take an openly negative stand toward California taxpayers, and especially the state legislature. Instead of expecting – or trying to mobilize – political support for public higher education, UC now blames public indifference for what it is now “forced” to do, and implies that a legislature that won’t pay should have no say over how UC uses the money that it “raises” on its own, such as tuition. Once UC openly declares its intent to use “its own” funds to raise more private funds, regardless of how much the state still pays, why should the state pay more?[11]

Should the State of California restore funding to UC? Of course it should. Otherwise, UC can’t continue as the great public university it still is. But, as a taxpayer, I would be reluctant to pay more unless UC also reverses course: it must, once again, be willing to use the revenue it holds in public trust to advance its state-mandated purpose. UC’s continuation as a great public university is impossible if advancing public higher education has ceased to be its own top priority.

Many will try to discourage you from becoming active in the effort to ”Save UC” by saying that its problems are typical of those facing public universities in the state and nation as a whole. They would encourage you to think that this is not the place to address these problems, or try to persuade you that now is not the time. But you should not conclude that, if a problem exists everywhere, it can’t be confronted anywhere; nor should you conclude that if a problem is ongoing, it can’t be addressed now. This is, in fact, a good place and time for us to confront a wider long-term problem. UC is a nationally prominent, and successful, public institution that has a deep reservoir of public support and a large body of students, faculty and staff who are ready to be educated and engaged in action.

There is also an immediate focus around which to mobilize—the Regents’ plan to raise tuition by 32% in November. If students, faculty and staff were to demand that funding public higher education be UC’s highest priority in the use of “its own” funds and assets, this would strengthen the moral case for restoring public funds.[12] My severest criticism of UC’s leadership is that it has lost (or given up on) the moral case that must be made for public higher education, which has, according to President Yudof, “lost its shine.”[13]

The fact that UC’s privatization reflects a national problem is not a reason to despair: it is, rather, a reason to make the fight against it our highest priority. The problem is here, the time is now, and we are building a movement that can produce new knowledge on which other movements could build. This kind of teaching and research in the public interest is what UC does best. Let it shine.

Want to know more? Here are answers to questions on this issue raised by skeptical faculty.

Projects funded by UC’s August 2009 General Revenue Bonds: [Amounts are not provided]

Berkeley

Biomedical & Health Sciences Step I

SAHPC (Stadium)

3200 Regatta Renovations

Clark Kerr Renewal

2007-2008 Deferred Maintenance

2008-2009 Deferred Maintenance

Law Building Infill

Anna Head

Davis

Physical Sciences Expansion

West Village Backbone Infrastructure

Health & Wellness

Graduate School of Management Conference Center

Project Augmentation

Tupper Hall

Hotel Site & Preparation

Building Jl Renovation/Upgrade

Cruess Hall Deferred Maintenance

2007-2008 Deferred Maintenance

Robbins Hall

Coffee House

Irvine

Engineering Unit 3

Social & Behaviorial Sciences

Stem Cell Building Gross Hall

Los Angeles

Life Sciences Replacement Building

Police Station

Hilgard Student Housing

100 Medical Plaza Building

Northwest Campus Student Housing Infill

Lake Arrowhead

Weybum Terrace

Pauley Pavilion

Merced

Merced Campus Parking Lot G & H

Riverside

Health Sciences Surge

Creekside Terraces

Summer Ridge Apartments

San Diego

North Campus Housing Ph 11

Health Sciences Grad Prof Housing

Cogeneration Plant Expansion

Muir Stewart Commons Renovation

Telemedicine

Revelle College Apartments

Muir College Apartments

Health Sciences Biomedical Research Facility II

Marine Ecosystems Sensing. Observation & Model

San Francisco

CVRI

NGMAN

Aldea San Miguel Housing Renovation

2006-2007 Deferred Maintenance

Santa Barbara

North Hall Data Center

Bio Science II Cagewash

Santa Cruz

East Campus Housing Infill

Porter College Phase IIA Seismic

Cowell Student Health Center Expansion & Renovation

2007-2008 Deferred Maintenance

Systemwide

Systemwide State Energy Partnership

FOOTNOTES

[1] UC’s plan to increase tuition-backed borrowing is large—I’ve read through the internal document (which looked like a PowerPoint printout)—but wasn’t allowed to keep a copy or take notes. I was, however, able to handle the document alertly, focusing on specific questions, because I had just written a draft of the present document, based on UC’s bond disclosures. I have, therefore, been able to revise the present document using at least some of the bond-related information that UC is presenting internally, but has yet to disclose. The UCOP handout is my basis for saying that UC is using tuition increases as a revenue source for debt service, and not merely as a pledge. It is also my basis for saying that UC plans to increase this use tuition to both back and pay off bonds.

[2] Since 2004, UC’s “General Revenue Bonds” have been backed by the bond proceeds themselves (of course). But, instead of being backed by the income from bond-funded projects, as most revenue bonds are, they are backed by UC’s “General Revenues.” This is defined by the Indenture (authorized by the Regents in July 2003) as follows:

‘General Revenues’ means certain operating and non-operating revenues of the University of California as reported in the University’ s Financial Report, including (i) gross student tuition and fees; (ii) facilities and administrative cost recovery from contracts and grants; (iii) net sales and service revenues from educational and auxiliary enterprise activities; (iv) other net operating revenues; (v) certain other nonoperating revenues, including unrestricted investment income; and (vi) any other revenues as may be designated as General Revenues from time to time by a Certificate of The Regents delivered to the Trustee, but excluding (a) appropriations from the State of California (except as permitted’ under Section 28 of the State Budget Act or other legislative action); (b) moneys which are restricted as to expenditure by a granting agency or donor; (c) gross revenues of the University of California Medical Centers; (d) management fees resulting from the contracts for management of the United States Department of Energy Laboratories; and (e) any revenues which may be excluded from General Revenues from time to time by a Certificate of The Regents delivered to the Trustee.” (Indenture, p. 11, as quoted in every subsequent bond Prospectus based on it.)

By pledging “General Revenues” as security for each UC revenue bond, the Regents are pledging everything that they can, including tuition. This means that when any source of General Revenue goes up—including student tuition and fees—UC’s ability to borrow on private capital markets goes up, and its dependency on state capital funding goes down, After 2004, any revenues produced by a bond-funded contract would be added to General Revenue (unless this were limited by that contract); but any such projects could also be subsidized by each other, or by revenues from sources such as tuition, student activities, grant “overhead,” endowment, etc.

NB. UC’s use of “General Revenue Bonds” does not preclude access to its traditional source of funding for capital projects, State of California Bonds. Many California bonds must be voter-approved; all are (in effect) approved by the Governor and legislature. UC-issued bonds are authorized only by the Regents, who make bond proceeds available to campus projects they approve.

[3] Yudof, “Why the U. of California Must Increase Tuition” (Chronicle of Higher Education, September 29, 2009).

[4] The General Covenant in the common Indenture for all post-2004 bonds says (See Indenture p. 16, and p. c-16 of the prospectus for UC’s August 11, 2009 bond offering)

[5] General Revenues include, essentially, all UC income that is not legally restricted by obligations to an outside party, such as the state, a contractor, or a donor.

[6] Mark Yudof, “Why the U. of California Has To Raise Tuition,” Chronicle of Higher Education (September 29, 2009).

[7] I didn’t think so, and I served on the UC Committee on Budget and Planning 2003-when it happened, along with Stan Glantz and Chris Newfield .We knew about, and objected to, UC’s agreement with Governor Schwarzengger to make UC increasingly tuition-dependent, but we were never told that the Regents had already voted (in July 2003) to use tuition as collateral for capital projects, which would allow more projects to be funded independently of the state as tuition rose. This The prospect of increasing freedom on the capital side, would have given the Regents a reason to seek tuition-sourced dollars whether or not doing so was part of a viable plan to fund UC’s operating budget.

[8] UC knows the full budgetary cost of federally-funded research. It negotiates the federal overhead rate by demonstrating that it loses money (overall) on this research. It then assures bond-holders that it is free to spend even less than it gets to support that research, so that 100% of its income for overhead can be added to the pledged collateral for new buildings.

Many of UC’s private sector research “partners” pay considerably less in overhead than the federal government (i.e., they are subsidized more heavily). They are also free to contractually obligate UC not to use whatever research overhead they pay for other purposes. Such contractual restrictions would keep overhead on these projects out of UC’s General Revenue Fund. UC’s private sector partners on the National Labs (Bechtel, et al.) seem to have made such arrangements, as has the DOE in its latest contract with that “partnership.” As far as I know, the terms of these contracts are still kept secret, at the request of UC’s corporate partners. You should demand to know what profits UC makes on these DOE contracts (which have doubled since UC took on corporate partners), and why profits from the lab partnership are not available to fund UC during an “extreme financial emergency” that requires cutting employee pay.

[9] I didn’t make up this argument: I heard it as a private aside from a UC administrator who was arguing in 2003-4 that taxpayers could no longer be expected to pay for higher education now that personal credit was so easily available. Times have changed, but UC has no new ideas.

[10] Bob Reich (“What’s Public about a Public University and Why That Publicness is Important?”)and Wendy Brown (“Why Privatization is About More than Who Pays?) enumerated these priority changes in their brilliant speeches on September 24, now posted on You-Tube. http://www.youtube.com/view_play_list?p=53D65B03FF28A6C7

[11] Remember that your activities fees, housing fees, parking fees, dorm fees etc. are also part of the pledge. Why? Because UC can tell bondholders that these revenues don’t have to be used for the purpose for which they are collected and because it has promised to raise these fees to whatever extent is necessary to maintain its bond rating. As students you can demand to know why your activities are being cut when there has been no reduction in fees, some of which were approved by student vote.

But all fees that have been pledged can be used for purposes other than those that justify them. The General Covenant in the Bond Indenture, repeated in every offering based on it, says that “So long as the Bonds are Outstanding, The Regents shall set rates, charges, and fees in each Fiscal Year so as to cause General Revenues deposited in the General Revenue Fund to be in an amount sufficient to pay principal and interest on the Bonds and …on Ancillary Obligations for the then current Fiscal Year.”

In case you’re wondering, however, I don’t think that all of UC’s activities should bring in enough revenue to pay for themselves. That test is part of privatization, although UC now treats privatization as self-justifying, and rarely turns down sources of revenue because they cost more than they return. I think on the contrary, that UC’s public mission can justify unequal expenditures to provide an equal education. By this standard a student should not pay more in tuition or fees for choosing a major that uses a biology lab rather than a dance studio, or, for that matter, my own traditional lecture room. So, I say “yes” to cross subsidies—but let’s use them for the purpose of promoting exchange and synergy among academic fields that are equally valuable, despite their different cost structures. That’s what great public universities do.

[12] The California Constitution specifically subjects the Regents to “such legislative control as may be necessary to insure the security of its funds” (Art. 9, sec. 9a.)

[13] “Big Man on Campus,” Questions for Mark Yudof, New York Times Magazine, September 27, 2009.

Posted: October 11th, 2009, by: admin. Categories: Uncategorized. 14 Comments.