by Bob Meister, President, Council of UC Faculty Associations

Professor of Political and Social Thought, UC Santa Cruz

(A PDF version of this document is available.)

Faculty colleagues have many questions about my open letter to students, “They Pledged Your Tuition.” Most of the questions come down to, “So what if students didn’t know that UC has been leveraging their tuition increases to fund more construction?” Let me formulate several versions of this question, and give some answers.

- Why should students care that their tuition is also used as bond collateral?

I clearly got my title right: there’s no question that since July 2003 UC has pledged student tuition (and other student fees) as part of the collateral for all the projects to be funded by General Revenue Bonds, which were first issued in 2004. I also gave students a clear enough explanation of what this means: that their tuition could be pledged because they can be legally obliged to pay it, but UC is not legally restricted in how to use it.

Much of my original letter was an effort to educate students about what UC’s bond pledge says with the exclamation points added. It says that UC could use tuition for any purpose; it also says that it would use tuition to repay interest and principal on bonds ahead of any instructional use. Beyond this, the indenture and every bond offering based on it include a “general covenant” requiring UC to raise tuition and fees as much as necessary to repay bond holders. Just before agreeing to this, UC also promises to do nothing that would cause its bond ratings to fall. Lower ratings would normally lower the price at which UC bonds can be sold before maturity. UC can protect its bond rating, while borrowing more, by adding to pledged collateral; but the only components of collateral under UC’s control are tuition and fees. This is why raising tuition and fees is the only concrete action UC promises the bond trustee and ratings agencies as part of its bond pledge.

Most students wouldn’t know that the increases in their tuition automatically add to UC’s collateral for construction bonds—and that UC can add collateral faster in years when state funds are cut. Why? Because higher tuition could be used to pay for what state education funds no longer cover, and many students want the most visible instructional cuts to be reversed. In my Open Letter I explain that this may not happen because the Regents see tuition revenue as a capital asset of the UC, and not as a straightforward replacement for state educational funds, which are not bankable in this way. Now that they know this, students should question how much of the 32% tuition increase will be used to restore educational cuts that UC blames on the state, and whether they would tolerate any increase as long as buildings are UC’s highest priority.

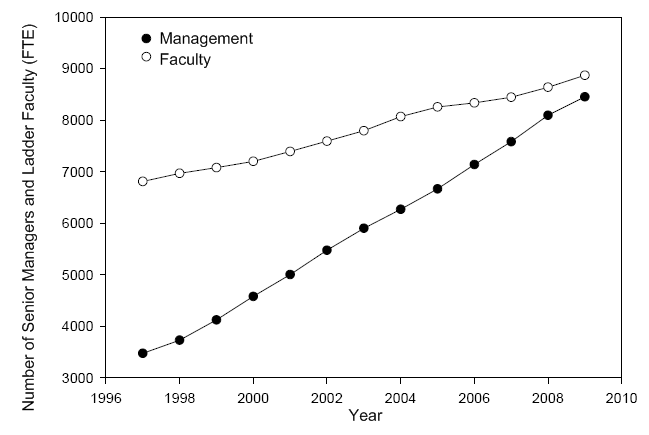

Since writing my letter, I can tell students much more than that UC could and would use tuition in this way: I can tell them that it has done this, roughly doubling the amount since 2008, and that it plans to do much more—beginning with another $2B bond issue that the Regents will announce after the 32% tuition increase in order to fund projects that they have already approved, but not announced. This information appears in a presentation by CFO Peter Taylor on October 6.. His slides show that General Revenue (i.e., tuition-backed) bonds provide UC with a rapidly growing capacity to take on more construction debt at favorable interest rates, and recommends that UC take advantage of this borrowing opportunity. This is how tuition increases look from his perspective, but not from a student perspective. They should be told that their tuition increases will allow UC to make construction a higher priority, whether or not instructional funding benefits.

- Even if it’s clear that tuition increases add to UC’s bond collateral, how do you know that tuition revenues are also being used to repay UC bonds?

This is a fair question based on my Open Letter to students—the very question I was urging them to ask. My letter distinguishes between what one pledges as collateral for a loan and what revenue stream one identifies as a source of repayment. As a rapidly-growing UC revenue stream, tuition could be either or both. I suspected that tuition could be both, but I wasn’t sure based on public available documents that tuition was being used as more than collateral. Peter Taylor’s presentation clearly shows that tuition is also the primary source of revenue for debt repayment, and recommends (for obvious reasons) increasing use of bonds that can be repaid in this way. The debt service on recently issued bonds, and new ones already in the pipeline, will have doubled to c. $435M between 2008 and 2012—a period in which tuition may also double.

If you think about it, CFO Taylor’s increased reliance on tuition as a way to repay bonds is obvious. State funds can’t be used for this purpose as a matter of state law; the “direct cost” portion of research contracts can’t be used for either debt collateral or for debt repayment because its use is restricted by the research contract themselves. Research “overhead” is never sufficient to cover the full cost of research, which UC is expected to “share” as part of its mission. Only bond-funded projects that bring in user fees, like parking garages and dorms, can be expected to pay for themselves. So what else is there but tuition to pick up the slack? And then, there’s the fact that UC has been allowed, since 2004, to increase tuition at will.

Do you have any doubt that the use of tuition for debt service will increase as tuition increases and UC borrowing against it also increases?

- How did this use of tuition revenues come about?

UC has made no secret of its desire to raise tuition. It told UCPB, when I was on it, that tuition was much too low, based on market factors that were independent of state budget cuts or increases. Under Gray Davis, however, UC was still concerned that continued state funding depended on its visible reluctance to raise tuition too fast—that eagerness to charge what the market allowed would provoke state cuts. UC’s long-term strategy was thus to raise tuition (which was too low anyway) in response to state cuts, so as to avoid retaliation, and to do this regardless of whether higher tuition would be used to restore the losses in instruction that seemed to necessitate it. Not restoring these losses was, I would argue, part of UC’s strategy, insofar as the continuing threat to other people and programs was part of its argument for the further tuition increases that UC wanted to impose anyway. Saving people and programs was, therefore, not UC’s first priority in using tuition increases: its first priority was to strengthen the case for further tuition increases. This strategy explains why President Dynes leapt at the opportunity afforded by Governor Schwarzenegger to accept permanent cuts in state funding in return for permission to raise tuition indefinitely without reprisal, and why the 2004 Dynes/Schwarzenegger Compact was such a turning point in the history of UC privatization.

Did Dynes and Schwarzenegger also, secretly, agree that UC could use tuition revenue, as it grew, to build whatever it wants independently of state bond funds? I don’t know. At the time of the Compact, UCPB was not told that was part of the deal, and was unaware that higher tuition in any amount would give UC more leverage to fund construction on its own. But maybe Schwarzenegger knew that this would sweeten the deal for Dynes. The tuition pledge had been adopted at an open Regents meeting, where Professor Charles Schwartz objected on the grounds that what has happened could happen. At that time, the tuition revenues -available to fund construction were less than half of what they are today, and General Revenue Bonds could be seen as a way to refinance existing bonds that already paid for themselves. So in 2004 the Regents could have said that including tuition in UC’s bond pledge provided investors with more diversified collateral, reducing risk lowering interest rates. It’s hard to argue now that this was its only effect.

My Open Letter asks UC students to demand proof that lower interest rates was the only effect of pledging tuition before going along with the next increase. Some students may choose to understand the link between higher tuition and construction growth as a conspiracy. To me UC’s policy would be just as bad if it had come about through a series of unplanned, opportunistic decisions made by people who had no interest in resisting privatization, which they saw as UC’s long-term future.

Did some UC decision-makers wrongly profit from these decisions? Others can investigate this question. Do all UC decision-makers benefit from privatization? Yes, after 2004 their pay scales were reset to match private sector compensation, rather than compensation in state agencies. For top administrators, privatization has already happened. And privatization is the problem.

- Why is it wrong to make UC’s richest students pay for new construction through higher tuition? Are they the only students harmed?

UC’s median student is even more greatly harmed. That student (or his/her family) must borrow more to pay for higher tuition. UC’s 2004 capital plan was in fact based on the assumption that, as the home mortgage and student loan industries were expanding, the median students could and would borrow more into the indefinite future. Today, UC expects median students and their parents to take on long-term debt at very high interest rates, ever-higher as their credit ratings go down, so that UC can borrow from Wall Street at 4.6% by issuing Aa1 bonds. This looks like one of those mispriced credit swaps—but it’s not really a swap at all for the median UC student who has little choice. This is what UC implicitly communicates to bond raters when it demonstrates its ability to raise tuition indefinitely, and to substitute out-of-state-students who will pay even more for in-state students who are unwilling or unable to finance the next tuition increase through assuming increased personal debt. Median students who borrow more will end up paying much more for their education (including debt service) than richer students.

I heard that UCOP plans to answer my “charge” by appointing a team of “experts” to explain that it’s normal for organizations to financialize as much as possible and to shift their credit risk onto others if they can. The experts don’t need to persuade me, I know it’s normal. I also know that whether they can do this is, and ought to be, a political question. UC is still a public institution that can be made to answer political questions publicly. We should ask these questions before it is too late.

- Does UC’s tuition-backed method of bond financing affect what gets built?

It leaves UC much freer to build projects that don’t pay for themselves without having to increase its endowment. UC has in effect leveraged its post-2004 freedom to raise tuition in order to borrow a pseudo-endowment that is now projected to reach $8B and will be unrestricted in its use. This is in contrast to UC’s actual endowment which is around $5B, almost all of which is donor-restricted. (Unrestricted endowment income is part of the General Revenue pledge.)

- So why isn’t it smart to borrow a larger endowment that the Regents can use as they please?

UC’s financial planners probably think they’re being smart, partly because they can use this borrowed money for projects that no longer have to earn the revenue that provide their principle source of repayment, which is now tuition. UC has used General Revenue Bonds to refinance existing bonds at lower rate of interest, which seems smart. I don’t doubt that these refinanced projects (including student dorms and parking lots) did pay for themselves—they had to show bondholders a favorable ratio between the additional cost of debt to the university and the additional revenue brought in by the funded project. That’s why UC issued its pre-2004 bonds for projects such as dorms.

Since 2004, however, all projects funded by General Revenue Bonds are funded by all General Revenue. This means that UC no longer published a debt service coverage ratio (net revenues divided by debt service for the year) for any project funded by General Revenue Bonds. Why? Because the principal source of repayment for all of them is student tuition across the UC system as a whole. To the extent that these bond-funded projects no longer have to pay for themselves, they will simply be a drain on increased tuition income that won’t be used for education and research. If UC were to publish a single debt service coverage ratio for all General Revenue Bonds, it would be conceding my point: that all construction projects funded in this way are subsidized by tuition and tuition increases.

- Are you sure that projects funded by General Revenue bonds don’t pay for themselves?

I can’t say this for sure based on public documents alone: I can only show that they no longer have to pay for themselves. The burden is now on UC to prove otherwise.

Can UC prove otherwise? It would be easy if it were true. Charles Schwartz, a retired Berkeley physics professor, has just last week requested debt service coverage ratios for all individual projects funded by General Revenue Bonds, as it does for project-specific bonds. Maybe UC still requires that adequate debt service coverage be demonstrated before it approves any new projects, even if the bond-raters no longer ask this question because they are paid from tuition. I’m sure UC could easily show debt service coverage for parking lots and dorms. It would be much harder for UC to shows this for other bond-funded projects, like administration and telecom buildings (and the Berkeley stadium) unless it conceives of students as paying a virtual rent on these buildings out of their tuition. The disclosures of such “shadow” accounts for each project would, however, prove my point by showing the exact amounts of tuition that are diverted from instructional use to support these projects.

What other lines of defense might UC take? I’m sure I haven’t thought of them all. One conceivable argument is that all projects funded by General Revenue Bonds should be heavily subsidized by tuition and fee increases because they were necessitated by enrollment. This argument could be sustained if General Revenue Bonds were in fact limited to projects necessary to accommodate enrollment growth. The revenue source used to repay these bonds—higher tuition from a larger number of students—would then be closely aligned with the purpose for borrowing. It’s clear, however, from the eighteen supplemental bond indentures that only some of UC’s bond-funded projects could be justified in this way. How much? The indentures do not show what portion of bond proceeds goes to each project: all the projects are funded by all the bonds. And, none of the indentures attribute revenues to specific projects, which, insofar as they exist, will simply be added to the General Revenue fund used to repay all bonds. If UC argues that it exists for the benefit of students whose tuition should be used to fund whatever it chooses to do, it will have conceded that my analysis is right. Students will then be entitled to ask whether UC’s choice of construction projects justifies increasing their tuition.

What other information could UC offer that would answer their question? There may be internal documents I can’t imagine that others have seen. Until I see these documents, I must, sadly, assume that keeping up UC’s overall construction program has higher priority than funding the educational needs created by enrollment growth. I wish I were wrong.

- Do we know how much these bond-funded projects drain from education?

The short answer is that we can’t know based on public documents. We know that interest on tuition-backed bonds will rise to c. $425M in the next 2-3 years (based on currently-approved projects) and that tuition will pay most of this interest. Whatever revenues these projects actually earn will be added to the General Revenue fund in categories of research overhead, user fees, etc., which are lower-ranked than tuition as a source of repayment. These General Revenue Bonds can be used to fund projects that don’t bring in additional General Revenue at all; they can also be used to fund projects that might reasonably be funded by student tuition or fees, such as classroom buildings, dorms or student centers. But now that all projects are funded by all student fees, student fee increases can be used to subsidize any project on any campus. The amount of this budgetary subsidy, which only begins with debt service and can encompass all losses associated with these projects, is the true educational cost of UC’s approach. To discover all these losses, we would need to drill down to the campus in order to see which programs have been cut (or ‘taxed’) the most to support new construction that does not specifically benefit them.

A clear example is UC Berkeley’s new football stadium, which will be financed by tuition-backed bonds. It’s conceivable that UCB has a debt service coverage ratio showing that it could have issued a “stadium bond” that would pay for itself with revenues earned. If so, it should share this analysis with the 49’ers. What if the stadium is not being financed by revenue from Berkeley football, but by tuition increases across the whole UC system? The rationale must then be that it adds luster to UC’s “brand” for which all students should pay. What does this say to other campus chancellors? It says that they should propose construction projects that enhance UC’s brand regardless of how much they drain funds from education, because such projects will certainly be built somewhere and will drain educational funds across the system.

- Should construction come first, even for students?

UC may have market studies showing that new buildings help its “brand,” and that curricular cuts don’t hurt its “brand.” If such studies are the basis for its present priorities, let it say so. Students and faculty can then judge for themselves whether UC’s “brand” is more important to them than the quality of education they actually receive (and can give). In my opinion, a choice in favor of education would do more for UC’s “brand” than keeping planned construction projects on track.

- Are construction projects bad?

No, I hate the classroom in which I now teach, and try to get my classes scheduled in the new, mostly science, building on the UCSC campus. But I would rather have TAs.

- Doesn’t UC get a lower interest rate by adding tuition to the pledge?

Yes, in 2008 it paid .2% less in interest for tuition-backed bonds than it paid for slightly-lower –rated bonds that were backed by revenues from specific projects.

- Wouldn’t UC have to use tuition to cover all its bonds if other pledged revenue stream were insufficient? If so, why not pledge tuition to get a lower interest rate?

If I understand this question correctly, it’s based on a spurious argument. The kernel of truth in this argument is that UC bonds are backed by something more than the contingent property right (lien) that bondholders have in the pledged collateral. If the pledge were insufficient, the loan document could also be enforceable against UC as an ordinary legal contract. The only way that UC could renege on this contract would be to threaten bankruptcy, which bondholders might be willing to avoid by taking what Wall Street calls a “haircut.” The spurious argument is that if UC could have paid bondholders out of tuition as an alternative to renegotiating its debts, then it makes no difference for it to pledge tuition upfront in order to reduce the likelihood of such a scenario.

These are, of course, completely different scenarios. UC issues secured debt for its construction projects, not unsecured debt (Commercial Paper) that requires it to keep a large positive bank balance but is otherwise much like a credit card. The fact that secured debt could revert to the status of credit card debt if the security vanishes does not justify UC’s General Revenue Bond program, which places something like a mortgage (really a lien) on student tuition. Consider the example of an ordinary mortgage in which the bank has a lien on your house, which serves as collateral. If your first mortgage is under water at the time of foreclosure, the holder of the second mortgage can try to collect against your paycheck alongside unsecured creditors, such as MasterCard.[1] Does this mean you should pledge your paycheck as part of every mortgage, so that the bank can be assured of a more diverse source of funds for repayment? Most people wouldn’t pledge their paycheck. Why? Because in a real emergency they would want to pay for other things first. The bank would not necessarily be their highest priority.

UC has in effect pledged its paycheck (the portion it is free to sign over), but wants you (and more importantly students) to believe that it isn’t actually drawing on this paycheck to fund whatever it chooses to build. This pledge clearly commits UC to raise the collateral it controls (tuition and fees) to whatever levels the rating agencies require. What other effects does it have? Wouldn’t pledging your own paycheck in this way affect your budget (spending) priorities? Wouldn’t collateral of this kind reduce the lender’s concern with whether the loan proceeds are used for a project that pays for itself or a project that drains other revenue? Wouldn’t the bank’s right to seize your whole paycheck in the event of default reduce its concern with whether your use of the loan proceeds generates new income sufficient to pay it back? Surely it would be satisfied to know that you have the power to raise paycheck at its request. UC gets its Aa1 bond rating by demonstrating its ability to do this, and not by demonstrating that its construction projects are good investments.

My question is whether UC’s pledge of tuition has changed it budgetary priorities away from curriculum and toward construction, and whether this method of financing makes UC unaccountable for the drain that construction projects place on curriculum during a financial “emergency.”

It’s a question of priorities, and of values.

- What’s wrong with UC’s values?

Nothing is wrong with the value of public higher education—UC’s leaders need to articulate that value, as Clark Kerr once did, as something that can be even better than the best private education. Why? Because Kerr’s Master Plan for Higher Education both expressed and aroused the desire for higher education as the pre-eminent common good that all Californians can in principle enjoy—a value added to the many uses education has for private advancement. UC’s specific role in the Master Plan is thatthe education it offers as equal to the best anywhere—and potentially even better because it also serves a public purpose

It is thus an article of faith for many Californians that UC is still great, and even greater because of its values. UC leaders have often urged me to suppress my criticisms, not because they are wrong, but because they would shake the public faith on which UC depends.

My underlying argument is that proponents of UC privatization both rely upon and betray the public’s willingness to believe that UC’s values are not changing—that it simply needs new sources of funding to do what it has always done. Californians need to know that a tuition-dependent UC will have its priorities driven by financial markets rather than by citizens. This means it will use the revenue streams from present activities, especially revenues that it can raise, to invest in new non-educational “initiatives” and “partnerships” that drain funds from UC’s Master Plan Mission.[2]

Faculty who oppose UC’s present run to privatization need to draw on the willingness of Californians to believe that UC is still good because it’s still public. We demand that UC be accountable for all its funds, not just its state funds, and that it become more, not less, transparent about its priorities as a public trust during a financial emergency. Is funding public higher education the highest Regental priority for the use of the vast, accumulated assets that they regard as their own? Or is public higher education now merely a contractual service they provide to the extent that the state is willing to pay them for it?

I wrote first to students, and not to my faculty colleagues, because I think that Regental accountability should begin with tuition, and with the 32% tuition increase now proposed. UC officials who deal with Wall Street will, of course, tell the Regents to regard tuition revenue as their own money, unlike state funds, which are restricted as to use. The Regents will do this because they can—because from the standpoint of the financial world UC is already private (it belongs entirely to the Regents) except for the $2.6B in educational funding it still gets from the state. Has UC’s public mission become an exception within a broader set of priorities set by the private sector? Is higher education something that Californians must now bribe UC to deliver? I hope this has not happened yet.

Questions about tuition—its use and the reasons to increase it—are, I think, the first place to test Regental priorities for the use of non-state money, and eventually all UC’s money. That’s why I’ve urged UC students to take these questions to the November Regents Meeting at UCLA.

October 19, 2009

FOOTNOTES

[1] My example is hypothetical. The rights of second mortgage holders to enforce their loan contracts depend on state law and the terms of each loan document.

[2] President Yudof’s New York Times interview of September 27 2009 suggests that UC received a lot of public investment to feed the aspirations of my generation, the baby-boomers, and that most attractive public investments now lie in providing geriatric care for us. This is, of course, how a fund manager would think in deciding where to reinvest the capital that can be raised by leveraging tuition.

As CPB Chair at UC Santa Cruz, I heard a similar suggestion about how to “leverage” major campus “assets”: alumni loyalty and a magnificent ocean view. The answer, discussed seriously, was selling burial plots for rich alumni from the 1960s and 70s who were disillusioned by campus change. I suggested that our graveyard be called “Sunset College: Where the 60’s Never Die.”

Posted: October 19th, 2009, by: admin. Categories: Uncategorized. 1 Comment.